Motivation

The Right Kind of Carrots?

Motivation can be hard sometimes! Even when we know what we want to achieve, and we understand what action is needed to make it happen, sometimes we can find ourselves holding back and procrastinating. What can we do to get over this self sabotage? And when we need to motivate others, how can we lead them to the right kind of actions?

1.Understanding the drivers

Since motivation is about internal processes as much as external rewards, it can be useful to unpick the thoughts and feelings and the underlying assumptions and values that hide beneath our observable behaviour. Let’s take for example, Susan, age 35. Susan wants to make a career change and has taken on a commitment to study law. However, when it is time to study for an exam or produce an essay, even though the topic interests her, she will suddenly find 101 other things to do instead of studying. Why do we often procrastinate like this?

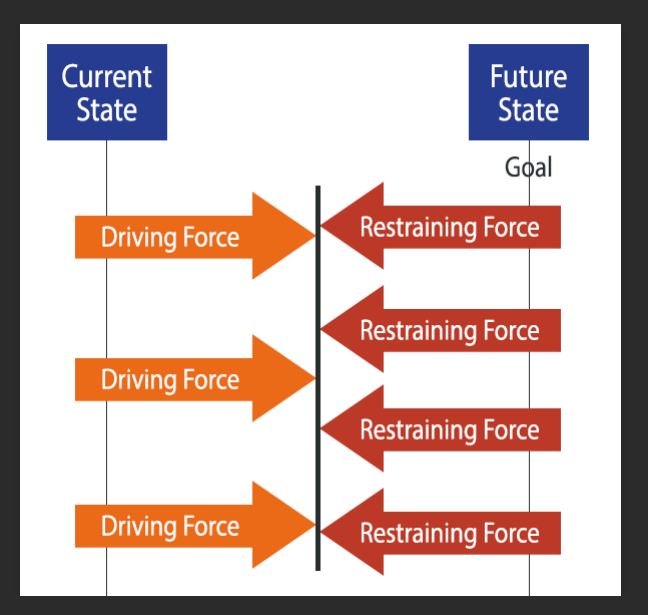

Social Scientist Kurt Lewin believed there were forces in multiple mental ‘fields’ of experience at play. He came up with a useful model in 1951 for capturing the competing interests in any endeavour. The central line in figure 1 represents the level of progress. The orange arrows represent positive forces, moving towards the ‘goal’ represented by a line to right hand side. The position of the middle line will move either closer to the goal or further away dependent upon the net position of Driving forces – Restraining forces.

In Susan’s case, her interest in law would be one of the orange arrows. Her future opportunity to become a successful practising lawyer would be no 2 and an impending deadline, and associated penalty if the deadline is missed would be no3. So these would all be positive drivers for her to study. However, she has more reasons holding her back. A lack of confidence could be one, another could be the fear of missing out socially while she is studying. The third and fourth red arrows could be a worry that she doesn’t understand this topic well and a genuine concern about getting behind with other household tasks.

2. Changing the inputs to change the outcome

Now that we have broken down and understood the restraining factors, we can take action to minimise them.

Extra time with her tutor could fill in any knowledge and confidence gaps Susan has. Scheduling some quality social time for after the deadline could take away the fear of missing out socially. Delegating some of the household chores would remove the nagging guilt that she is feeling about how she “ought to put the washing on”. These actions would weaken the restraining factors’ power.

Alternatively, Susan could work on strengthening the positives. If the idea of practising law feels distant, she could perhaps shadow or get some voluntary experience now to make the experience of practising law stronger in her mind. If she gave herself interim goals such as set a closer deadline for the first draft, this may bring the sense of the deadline more to the fore.

3. Activity: Pick a goal you are working towards and use the worksheet to split down the ‘for’ and ‘against’ factors at work. Identify what actions you could take to redress the balance and make more progress.

4. Motivating Others

When it comes to motivating others to action, we can use the combination of the model above, and the idea of ‘carrot and stick’ to understand factors affecting behaviour change. Some change theorists have focused on the need to create a “burning platform” – ie a strong cautionary message about the negative consequences of maintaining the status quo. If you are interested to find out more about the background to this analogy, there is a useful reflective article here by Daryl Connor, the man who first introduced the term to the business environment.

I use the burning platform as a metaphor for the unwavering commitment needed to sustain significant change.

Darryl Connor

A ‘burning platform’ is not always necessary to initiate action. If a positive vision of the future goal is strong enough then the ‘pull’ of its appeal will negate the need for ‘negative’ motivation factors. Think of the athlete focused on winning gold. She does not occupy her mind with thoughts of failure. She simply focuses on the positive goal.

One successful business embodiment of this ‘carrots only’ approach is the US accessories company Stella & Dot. Founder and CEO Jessica Herrin built her brand around her vision and values about flexibility, choice and independence. The positive rewards of joining in that vision are supplemented with tangible ‘prizes’ for success. There are no disincentives applied for failing to meet particular targets, and ‘stylists’ are free to work as much or as little as they would like. Stella & Dot successfully harnessed the power of the social peer-group by creating a community of stylists who encourage and support each other to achieve. Her organisation was able to successfully build a social selling company which reached $1m sales in it’s first 2 years and expanded ever since, reaching $100m by 2010. Jessica gave some advice for other business leaders on motivation here.

5. Pyramids and Icebergs

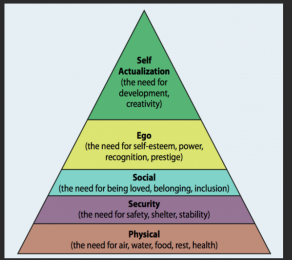

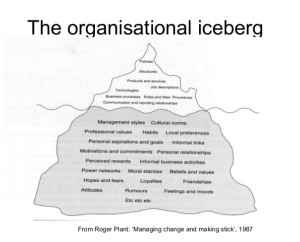

There are at least two other primary motivation models which are useful to consider when assessing how best to motivate yourself and others. There is much more which could be say about these but this ‘mini guide’ article seeks only to introduce them. These are i)Maslow’s pyramid of the hierarchy of needs, and the ii)iceberg concept of conscious and subconscious drivers in behaviour. There are various versions of the iceberg model but here we will simply introduce one by Robert Plant from his 1987 book “Managing Change and Making it Stick”

The iceberg introduces the idea that the visible behaviours and acts are only a small part of a much bigger picture. Underneath what can be seen and physically demonstrated, our conscious behavioural choices, lies a vast array of factors influencing us on a much more subtle, often subconscious level.

For example, an ethical sales manager asked to sell products he does not believe will benefit his clients, will have a constraint to his motivation and performance because to sell these would go against his professional values of doing the best for his clients. Even if he needs the job and convinces himself to do it, he will not be as successful as if he were selling a product which aligns with his inner values. Even when we are not aware of them, a lack of synchronicity between our conscious and subconscious beliefs causes us to appear less trustworthy and to limit our own success in the anachronous behaviour.

Your subconscious mind also practices homeostasis in your mental realm, by keeping you thinking and acting in a manner consistent with what you have done and said in the past. All your habits of thinking and acting are stored in your subconscious mind. It has memorized all your comfort zones and it works to keep you in them.

Brian Tracy

Maslow was a psychologist rather than a businessman, but his model has been applied to retention and reward policies for decades. His ‘hierarchy of needs’ theory provided a a way of structuring which factors are most important to individual motivation at any given time. It is often referred to in design of corporate reward structures so that these are not solely based on financial reward, but appeal to security, social and ego needs for example.

Summary

Motivation is complex due to the interaction between extrinsic environmental factors and the internal hidden intrinsic/subconscious factors which can influence our behaviour. However, we need are not powerless in the face of these and should not be put off by the complexity. By unpicking and identifying the various factors involved, we can simply take action to align and adjust the balance of forces in the direction of progress. Or change our goal if we decide there are other stronger preferences to focus on.